Twisted Tracks of Love:

Modern Marriage

Book Review &

Exclusive Behind The Scenes Interview with Author

Ivelisse Rodriguez

Modern Marriage

Book Review &

Exclusive Behind The Scenes Interview with Author

Ivelisse Rodriguez

|

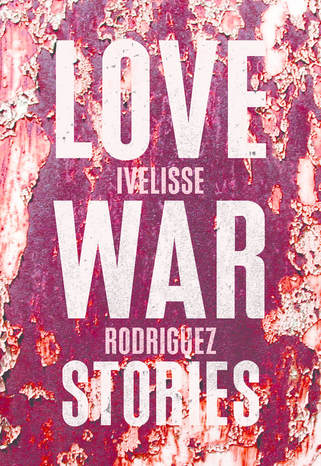

When Anna first falls head-over-heels in love with Vronsky, we all swooned, believing that their love was all that they needed to free them both from a passionless life. We believed that their love, complicated by her husband, was the only thing they needed as they quickly disavowed money and stability. Tolstoy’s novel quickly became a cautionary tale, introducing role models both we longed to be and hoped we’d never become. Like Anna, we often realize that a successful relationship needs a stronger foundation. Flash forward to a society filled with failed relationships and several unsuccessful Tinder dates and it no longer seems possible that love would find us and sweep us off of our feet. Cynicism aside, today’s love and dating scene is difficult to navigate and rarely leads to everlasting love; Ivelisse Rodriguez’s “Love War Stories” (LWS) explores the intricacies and inherent contradictions of modern love.

|

|

|

The novel was published by the Feminist Press in July. Rodriguez stunningly manipulates the line between reality and fiction in the pursuit of lasting love. Love, a concept that many find foreign today, is resurrected through daring and reflective prose. She expands on Nuyorican literature, a genre in which Puerto Rican authors and poets discuss migration and a split identity between the United States and Puerto Rico. She dives into the intense and complicated world of modern love, incorporating themes of femininity and identity seamlessly from story to story whether through a crusade for love or through their culture.

Each story follows a young Latinx coming-of-age story, as they struggle to define themselves. Readers will discover cultural and societal contradictions and myths about the meaning and value of love and marriage. Accessible to all readers, Rodriguez incorporates modern feminist concepts such as sex positivity for all genders, allowing readers to empathize with each character. Several stories question the meaning of womanhood in its various forms, and its association with love. Others show a side of love not often shown; one that leaves characters damaged. Rodriguez tempts readers with a debate about the benefits of love in the titular story, “Love War Stories”. While the younger generation at first strives to find love in all relationships, their mothers warn them about the potential damage to one’s sense of self. LWS allows readers to explore both arguments, as well as how a society can affect the ways that womanhood is perceived.

In two stories, Rodriguez incorporates Puerto Rican poet and founder of the Nuyorican movement, Julia de Burgos’s poetry. De Burgos explores the ways that a woman can belong to others, while still seeking independence from the bonds. To be outside of one’s culture is a common theme in the genre, but Rodriguez expands on the feeling of “otherness” in another culture to include the contradiction of becoming a woman. Marginalized women, like de Burgos, who didn’t fit the mold of a typical woman, are paired up with women who strictly follow a culture’s opinion of what a woman should be. De Burgos, as well as other characters within the anthology, exhibit sex-positive behavior unseen in other Nuyorican literature.

“Love War Stories” is one of the best novels I’ve read in awhile. Rodriguez incorporates womanhood, identity, culture, and modernity to form an accurate portrait of love for many Puerto Ricans living in America. Her stories are accessible to women and men who enjoy reading novels featuring multicultural and dynamic characters. Her writing abandons formality and prefers a sense of camaraderie with the audience; the characters feel more like old friends than words on a page. Horrible Tinder dates aside, “Love War Stories” exemplifies the hope we feel on a good date: engaging banter, light humor, and the unmistakable desire to find love.

Born in Arecibo, Puerto Rico, Ivelisse Rodriguez grew up in Holyoke, Massachusetts. She earned a Ph.D. in English-creative writing from the University of Illinois at Chicago. She is the founder and editor of an interview series published in Centro Voices, an online magazine of the Center of Puerto Rican Studies, focused on contemporary Puerto Rican writes. She was a senior fiction editor at Kweli and a Kimbilio fellow. She is currently working on a new novel, “The Last Salsa Singer” about the story of a friendship in the forefront of salsa music in Puerto Rico.

|

|

Interview with

Ivelisse Rodriguez

Ivelisse Rodriguez

Photo Credit: www.masterteacherscollective.com/ivelisse-rodriguez

MM: What was the first book you read?

IR: I don’t even know. I remember reading Judy Blume and Beverly Cleary. How old are you in third grade, like eight? I just remember always reading. I mean, obviously, not when I was three, but I don’t know after that. While I honestly wasn’t like a constricted writer. For a long time, it was this thing that I said I wanted to do, but I didn’t do. And then, I took, maybe two creative writing classes in college. And then, I don’t know why but I applied to M.S.A. programs and I got into one, so, “I’ll try this”. I still needed to learn how to write more after the program, and that’s not their fault. And then I got my Ph.D. in creative writing and my writing was becoming stronger. A lot of times I was scared, or fearful of facing the page, where like you go to write, and are just consumed by fear and then you don’t do it. In 2015 I quit my job, my full-time teaching job and I started working on a novel. The next year, I entered the Feminist Press contest, the Lewis Merryweather contest, and obviously, I didn’t win, but they decided to publish it anyways, and here we are….

IR: I don’t even know. I remember reading Judy Blume and Beverly Cleary. How old are you in third grade, like eight? I just remember always reading. I mean, obviously, not when I was three, but I don’t know after that. While I honestly wasn’t like a constricted writer. For a long time, it was this thing that I said I wanted to do, but I didn’t do. And then, I took, maybe two creative writing classes in college. And then, I don’t know why but I applied to M.S.A. programs and I got into one, so, “I’ll try this”. I still needed to learn how to write more after the program, and that’s not their fault. And then I got my Ph.D. in creative writing and my writing was becoming stronger. A lot of times I was scared, or fearful of facing the page, where like you go to write, and are just consumed by fear and then you don’t do it. In 2015 I quit my job, my full-time teaching job and I started working on a novel. The next year, I entered the Feminist Press contest, the Lewis Merryweather contest, and obviously, I didn’t win, but they decided to publish it anyways, and here we are….

|

MM: Last year, you were inducted into the Kimbilo fellows. You also have contributed to a magazine highlighting Puerto Rican writers. Do you think that organizations like these encourage new writers of color?

IR: Absolutely. Kimbilio, it’s for writers of African descent. I think is what’s nice is that there are people that understand your stories and get certain things. I remember when I was doing my Ph.D. and there was an African American woman in my class, and there were all these hints of colorism in her stories, which I don’t think that other people got, but I did, I understand that. They’ve just been really supportive, and you get to hear other stories that you can readily identify with. It’s like your heart swells in these spaces. You just feel so comfortable and there’s just a level of camaraderie which I don’t experience in other workshops. Centro Voices, at the center for Puerto Rican studies, which I'm invested in Puerto Rican writers because Puerto Rican writing on the continent of the U.S. spans over 100 years. That and Mexican-American literature, I feel we laid down a foundation for other literature from other Latin-American groups. I do this interview series because I want to showcase Puerto Rican writing and to study what the new trends are in it. I just thought I don’t want to write these stories about migration and missing a homeland, and talking about how cold it is in the U.S. You see that a lot in the early works like in the 1970s with the Nuyorican poets, with this schism they feel, between being the U.S. like feeling outsiders in the U.S. and then in Puerto Rico, with racism etc. We’ve spent at least 80 years talking about migration and so I really wanted to talk about something else and move Puerto Rican literature away from that and experience new things. MM: In your first story, “El Qué Dirán” you included a sample of the Puerto Rican poet Julia de Burgos’ writing. Is there any character within the anthology that you think exemplifies her message there? IR: I would say that it has to be Tía Lola, in that story. Because, almost like, I don’t wanna say the freedoms. When she realizes that her husband isn’t coming back for the child’s birth. She totally loses it. I think, at that point, she’s out of society’s bounds. She no longer cares about what society thinks and that’s why she’s wailing outside because she doesn’t care anymore. She’s the one that realizes that being a woman is a terrible thing and tries to save Noelia. She’s the one that belongs outside of society. Noelia, in the end, because her Puerto Rican moment of becoming a woman is taken away, now she’s outside of that society too. Because, by losing her virginity, it’s the American mode of becoming a woman. And that’s why at the end she’s shipwrecked, her whole world has imploded. So she’s out of [society], but it’s actually by force. What I took out of the story, now the men make fun of her. The poem is celebrating the women who step out of society, but there are these other people out of society, the crazy women, the prostitute, these women who have sex, so there can be those women who practice self-possession, or women that we might think are marginalized and are engaging in some other form of womanhood. |

|

|

MM: You address the idea of womanhood and growing up a lot in LWS. Was this a reflection of?

IR: I would think it’s a reflection of how some experience love. It becomes this force that you follow no matter what, it becomes this thing that’s more important than anything else, like how Vanessa chases after Ralfy. But the idea of love overshadows everything else. It's omnipresent...people thinks that’s the most important thing versus respect of care. I think there’s some trouble with this idea of love because I think that women especially end up sacrificing too much because they think that love is going to bring them all these good things but they also bring all these bad things. That’s what I wanted to show. MM: You’re being published by Feminist Press. There’s a lot of different definitions of feminism today, but some consider modern feminism the acknowledgment that women face different experiences based on a variety of identities, such as race, sexual orientation, gender identity, occupation, wealth, and a lot of other things. Within these guidelines, do you think that LWS can be classified as a feminist novel? IR: Oh yeah, absolutely. Love is so attached to women like it’s the bane of women. I want to show the way that women survive it, even if you think they didn’t. Like with The Belinda, Belinda is obviously broken, but in the end, she realized that she was the one that was changing all along. I think it’s important for women to focus on what they're really looking for when they say that they’re looking for love. Love can be damaging, and ultimately women have to learn that love isn’t the thing that’s going to save them. |

MM: In some of your stories, Holyoke, Mass: An Ethnography, and Hija Chango, you explore a divide between white and Latin-American communities. Do you think that there are some cultural differences between how people experience love and relationships?

IR: When I was thirteen, we were hanging out. Most of my friends were pregnant, not me. We had like, bodies, and stuff. And I would see white girls on TV, and they just seemed so young, in a sense. It was always weird to me, like a different thirteen. We had like, older guys after us, which sound bad now. It was so normal. (laughs). Again, there’s like this idea that you need a man, but men are terrible. That’s definitely a Puerto Rico thing. In Borderlands, by Gloria Anzaldúa, the girls had to be covered up when were they around their cousins or their uncles. Like all men are suspect, that even if you’re a little girl, you have to be careful around them. It’s that mentality and in other Latino cultures. I don’t know if other cultures have the same thing.

MM: I read somewhere that you’re working on a new novel about salsa music.

IR: It’s called The Last Salsa Singer. It’s about these two friends, Vicente and Richie. Richie is

lovestruck over Lucy….be the one to save her. Vincente is totally appalled by that. They had made this song making fun of their relationship and Vincente’s hope is that Richie will get rid of Lucy. And it ultimately becomes their most famous song...Vicente loses his legacy because he can no longer have what he wanted because of the song. Another part is how Vicente and the band made fun of Lucy, she’s just a girl, but she ends up destroying their lives. It’s also supposed to be about friendship, over romantic love. I want to talk about the other parts of love that don’t get talked about as much, but I want to position it so they’re more important than romantic love.